The Gordon Approach: Music Learning Theory

Wendy Valerio, Ph.D.

Music Learning Theory, researched and developed by Edwin Gordon from the mid 1950’s to present, is a set of ideas about how humans learn music through audiation. By breathing, moving, rhythm

chanting, singing, and playing instruments we develop audiation skills that allow us to give meaning to the combinations of rhythm patterns and tonal patterns that make music a unique form of

human communication. Moreover, audiation may be expressed in a variety of ways that may be developed sequentially from before birth through adulthood (Gordon, 2007a; Gordon, 2007b; 2007d).

Through audiation, we discover music learning as a never-ending, ever deepening process for music expression and enjoyment. Following is an overview of key Music Learning Theory components. This

overview is not intended as an in-depth description. For in-depth study information please visit http://www.GIML.org and http://www.sc.edu/library/music/spec_coll.html. (For further background,

refer to infomration at the end of this article.)"

Philosophy

Gordon bases Music Learning Theory on his extensive research in music aptitude, the potential each human has for music achievement (Gordon, 1965/1995, 1979, 1982, 1989a, 1989b). Music aptitude

and music achievement are different, but are closely intertwined. Whereas music aptitude is the possibility for music achievement, music achievement is the realization of that possibility.

According to Gordon, we are each born with music aptitude. As with other human learning potentials, there is a wide range of music aptitude levels distributed among the human population.

Moreover, both music aptitude and music achievement are dependent on audiation. That is, our music learning potentials and our music learning achievements are based on our music thinking. Most

importantly, that music thinking goes beyond mere imitation and leads to music comprehension (Gordon 2007b; 2007d).

Through his research Gordon (2007b; 2007d) has determined that music aptitude is developmental, fluctuating from birth through approximately age 9, and stabilized thereafter. The interplay

between the music aptitude we receive at birth and the music environments we experience during the first few years of life begins to account for the variety of individual music differences

teachers observe among students in their music classrooms. Teachers may use Gordon’s music aptitude tests (Gordon, 1965/1995, 1979, 1982, 1989a, 1989b) to identify each student’s music aptitude

and to adapt music instruction to address each student’s individual music strengths and weaknesses.

Ideally, during the first years of life, before music aptitude stabilizes we each receive rich, sequential informal music guidance followed by formal music instruction that allows our music

potentials to stabilize as high as possible, and sets the stage for music achievement. Gordon (2003, 2007a, 2007b, 2007d) explains that through informal music guidance and initial formal music

instruction we develop music vocabularies. Gordon likens the development of music vocabularies to initial language vocabulary development.

Music and Language: Parallels and Differences

Think about how a child learns a native language by developing five vocabularies: listening, speaking, thinking, reading, and writing. In utero, the typically developing fetus begins building a

listening vocabulary by perceiving and reacting to sounds. When out of the womb, the infant continues to deepen and expand the listening vocabulary as adults and children speak to the infant and

to each other in the infant’s presence. The breadth and depth of the infant’s listening vocabulary depends on the breadth and depth of language in the environment. The combination of heard

language variety and repeated language exposure allows the infant’s listening vocabulary to expand and become the foundation for all other language vocabularies (Gordon, 2007a, 2007b).

As the infant hears the sounds of language spoken in context and syntax, the infant begins to make vocalizations. At first, adults and children in the infant’s environment may interpret those

vocalizations as random noises. But with continually increasing expectancy that the infant wants to and will communicate using language, adults and children who try to communicate with the

infant, interpret those vocalizations as intentional language babble, language approximations, language imitation, and language improvisation through conversation (Reynolds, Long, Valerio, in

press). As the infant becomes a toddler, preschooler, and school-aged child, he uses language interactions with others to develop a thinking vocabulary, while continuing to absorb listening

vocabulary, to expand the speaking vocabulary, and to develop language reading and writing language vocabularies (Gordon 2007a. 2007b). By experiencing and making language meaning through

listening and speaking, the child gives meaning to notated language when reading and writing.

Gordon (2007a, 2007b, 2007d) posits that the types of music vocabularies a child develops are similar to those developed in language. In music, however, a child audiates music, rather than thinks

language, to develop those vocabularies. As a result the five music vocabularies are listening, performing, audiating/improvising, reading, and writing. Before birth, a child begins to develop a

listening vocabulary of music in the environment. When out of the womb, the infant continues to deepen and expand the music listening vocabulary as adults and children sing and chant to the

infant and to each other in the presence of the infant. The more repeated and varied music the infant hears, the deeper and richer the music listening vocabulary may become, and the greater is

the foundation for all other music vocabularies (Gordon 2007a. 2007b, 2007d).

As the infant hears the sounds of music performed in music context and syntax by adults and children, the infant begins to make vocalizations. At first, adults and children in the infant’s

environment may interpret those vocalizations as random noises. But with continually increasing expectancy, adults and children who try to communicate musically with the infant interpret those

vocalizations as intentional music babble, music approximations, music imitation, that leads to music improvisation and music conversation (Reynolds, Long, Valerio, in press). As the infant

becomes a toddler, preschooler, and school-aged child, he may use music interactions with others to develop an audiation/improvisation vocabulary, while continuing to absorb a music listening

vocabulary, to expand the music performing vocabulary, and to develop music reading and music writing vocabularies. By experiencing and making music meaning through listening and performing, the

child gives meaning to music notation when reading and writing (Gordon 2007a. 2007b, 2007d).

Preparatory Audiation and Audiation

Though children not may be born audiating, they are born ready to audiate. Ideally, the adults and peers in children’s environments nurture their audiation, music aptitudes, and music

achievement, from at least birth (Gordon, 2003, 2007a, 2007b, 2007d; Reynolds, Long, and Valerio, in press). Similar to language learning, as adults and peers guide children’s language learning

through interactions (Bruner, 1983; Vygotsky, 1978), children are dependent on those adults and peers to guide their music learning through music interactions. Initial music learning, like

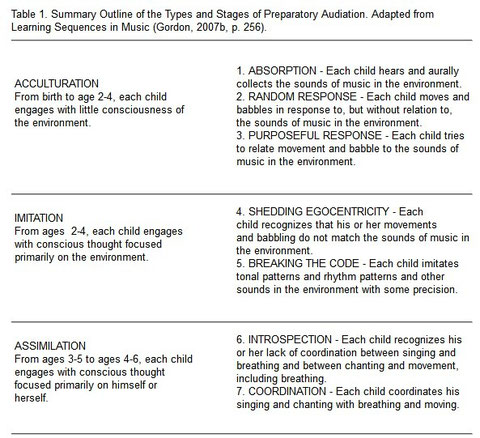

initial language learning, is informal, yet sequential. Gordon (2003; 2007b, 2007d) theorizes that there are three types and seven stages of preparatory audiation hough which children progress as

they are guided on the path to audiation. The types and stages of preparatory audiation are presented in Table 1.

Valerio, Reynolds, Taggart, Bolton, and Gordon (1998) describe informal music and movement activities that adults may use to guide children in the types and stages of preparatory audiation. As

with initial informal language learning, initial informal music learning takes place most naturally in child-centered, playful environments where music is a verb to be experienced through sound,

body and multiple human interactions (Reynolds, Long, Valerio, in press). When children are progressing through the types and stages of preparatory audiation, they engage in tonal and rhythm

music babble and music interactions. Through those interactions, adults and peers help children shape their music babble into objective music syntax. As a result, what may seem to be the

meaningless or random vocalizations and movements from infants, become recognizable rhythm chants and songs due to the music interactions children encounter with adults and peers as they progress

through the types and stages of preparatory audation. If guided, but not rushed children will typically exit the types and stages of preparatory audiation as they begin coordinating their singing

and chanting with their breathing and moving at approximately age 6 or 7.

Types and Stages of Audiation

As children develop their audiation skills, they may engage in music imitation as they learn rhythm chants, songs, rhythm patterns, and tonal patterns, but they also engage in music comprehension

as they compare the music they are hearing or performing to music they have heard or music they are predicting they will hear. Gordon (2007b) states, audiation is, “hearing and comprehending in

one’s mind the sound of music that is not, or may never have been, physically present. It is not imitation or memorization,” (p. 399). That is, audiation is music thinking, and music thinking may

be expressed in several ways that may involve, but go beyond, mere imitation.

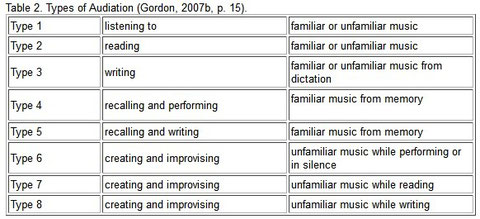

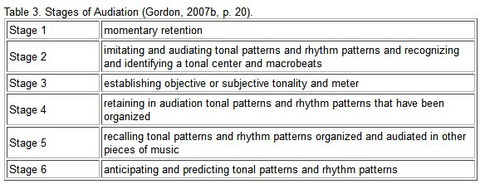

When audiating, children and adults may engage in eight audiation types and six audiation stages. Whereas the stages of audiation are sequential, the types of audiation are not. The types and

stages of audiation are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Music educators who use Music Learning Theory to inform their understanding of how humans learn when they learn music realize that the types of audiation are the bases for audiation expression

and may be used the bases for music assessment. When students express what they are audiating, that expression can be measured as a type or types of audiation with varying degrees of music

achievement. The challenge for the music teacher is to combine her knowledge of audiation with appropriate, sequential activities that promote the development of the types of audiation.

Music Learning Sequences

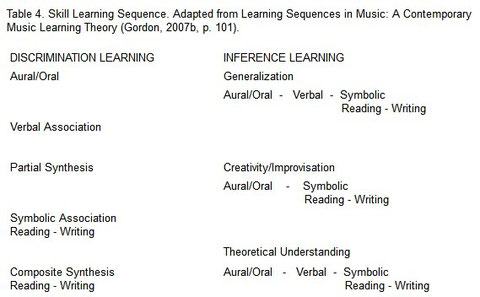

Gordon (2007b, 2007d) recommends using several learning sequences for optimal formal music instruction. Those learning sequences are: music skill learning sequence, tonal learning sequence,

rhythm learning sequence, and pattern learning sequence. Through music skill learning sequence students learn to discriminate among tonal patterns and rhythm patterns through imitation. As they

do so, they gain the readiness for inferential music thinking. Gordon outlines discrimination learning and inference learning in Table 4.

For tonal audiation development, skill learning sequence must be combined sequentially tonal content and tonal patterns. For rhythm audiation development, skill learning sequence must be combined

sequentially with rhythm content rhythm patterns. Gordon prescribes specific and separate sequences for tonal content and rhythm content learning. Within each type of development, however,

patterns of sound, not individual pitches or durations, are the focus. By audiating patterns of sound, students comprehend music context and syntax. Through the interaction of music skill

learning sequence, tonal learning sequence, rhythm learning sequence, and pattern learning sequence students give meaning to music as they engage in the types and stages of audiation.

According to Gordon (2007b, 2007d) learning sequence activities are the essential tools for tonal audiation development and rhythm audiation development. As outlined in the tonal and rhythm

register books that accompany, Jump Right In, The Music Curriculum, Reference Handbook for Using Learning Sequence Activities (Gordon, 2001) and in Jump Right In, The Instrumental Curriculum,

Band, Strings, and Recorder (Grunow, Gordon, Azzara, Martin, 1999-2002), teachers who use Music Learning Theory should engage their students in tonal pattern or rhythm pattern instruction during

5-10 minutes of each class period. As they do so, they will take their students through an audiation skill learning sequence involving a continual, sequential interplay between imitation learning

and inference learning, and introducing sound-before-symbol as suggested by Pestalozzi, Dalcroze, Kodály, Orff, and Suzuki. As they proceed through learning sequence activities, students gain

skills in major, harmonic minor, Dorian, and Mixolydian tonalities, and duple, triple, combined, and unusual meters.

Classroom Activities

As might be expected, learning sequence activities need to be coordinated with classroom activities where students are introduced to tonalities and meters, as well as other music elements.

Classroom activities may be of any type, including those from Dalcroze, Kodály, Orff Schulwerk, and Suzuki traditions, which allow teachers to introduce students to a variety of tonalities and

meters.

With all classroom activities, some general considerations are necessary for students to reap the benefits of audiation. First, for understanding and internalizing meter, tempo, and rhythm,

continuous movement activities, rather than beat-keeping activities, are most beneficial. Many continuous movement activities that emphasize the use of flow, weight, space, and time may be found

in Jump Right In, The Early Childhood Music Curriculum, Music Play (Valerio, et al. 1998), Guiding Early Childhood Music Development: A Moving Experience (Reynolds, 2005), Jump Right In, The

Music Curriculum, Teacher Editions, Book 1(2000), Book 2(2001), Book 3(2004), Book 4 (2006), and Buffalo: Music Learning Theory/Resolutions and Beyond (Gordon, 2006a). By participating in such

activities over time, students become adept at fluently measuring the space and time in and between beats in the music they are listening to or performing. Second, proper vocal technique is

necessary for the expression of tonal audiation. For all children, therefore, proper use of head voice must be emphasized, especially for tonal audiation development. Third, teachers must not

assume that students will automatically demonstrate proper breathing and posture. Above all, the teacher must model proper breathing, posture, and singing. Proper breathing and posture will

enhance students’ singing voice use and audiation.

Teachers and students who engage in sequential audiation development through learning sequence activities and classroom activities find themselves eager to participate in music improvisation as a

natural outgrowth of their music thinking interactions with each other. Through music improvisation, they own their music thoughts, express their music individuality, and deepen their music

understanding and enjoyment. For those purposes, Gordon’s (2003) Improvisation in the Music Classroom and Developing Musicianship through Audation (Azzara and Grunow, 2006) are useful

resources.

Combining Learning Sequence Activities and Classroom Activities:

Whole-Part-Whole

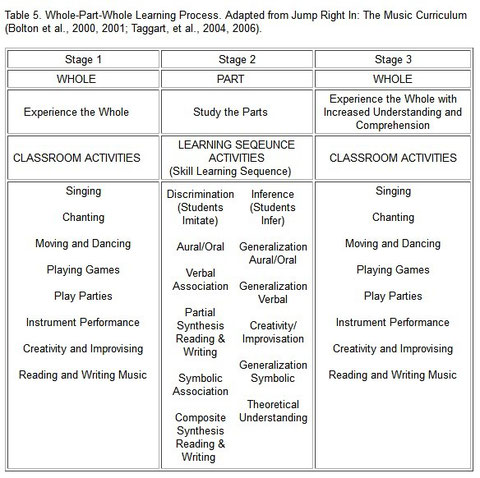

To combine learning sequence activities and classroom activities, a three-stage,whole-part-whole process is used so that students 1) experience music holistically, 2) examine the parts through

tonal patterns and rhythm patterns, and 3) experience music holistically again with increased understanding and comprehension (Bolton, et al., 2000, 2001; Taggart, et al., 2004, 2006). When

combining learning sequence activities and classroom activities, tonalities and meters are introduced in classroom activities, tonal patterns and rhythm patterns are examined and practiced with

regard to skills learning sequence in learning sequence activities, and tonalities and meters are experienced again in classroom activities. The three-stage, whole-part-whole process, adapted

from Jump Right In: The Music Curriculum (Bolton et al., 2000, 2001; Taggart, et al., 2004, 2006) is outlined in Table 5.

Solfege

When using Music Learning Theory tenets to help students learn music, Gordon (2007b, 2007d) recommends using two types of solfege: tonal solfege and rhythm solfege. Each type is used to assist

students as they compare, categorize, and classify tonal patterns and rhythm patterns, respectively, while using their audiation skills.

Because comparisons between tonalities are basic to tonal audiation development, Gordon recommends using movable-“do” tonal syllables with a “la”-based minor, “re”-based Dorian, “mi”-based

Phrygian, “fa”-based Lydian, “sol”-based Mixolydian, and “ti”-based Locrian. This tonal system allows students to recognize and audiate the characteristic patterns of each tonality without

prematurely resorting to notation and theoretical understanding.

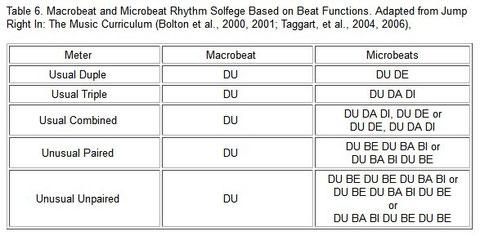

When students audiate rhythm, they compare rhythm patterns and meters, not individual durations. For that reason, Gordon recommends using rhythm solfege based on beat functions, rather than note

values. The macrobeat and microbeat rhythm solfege used in learning sequence activities is outlined in Table 6.

Theory, Method, Techniques and The Gordon Approach

According to Gordon (2007b), “The Gordon Approach” must not be confused with Music Learning Theory, method, or technique. Music Learning Theory is not a method, nor is it a set of techniques, but

teachers and curriculum administrators may use Music Learning Theory to develop their own music education methods, techniques, and curriculums grounded in audiation development.

Methods and techniques are unique to each teacher. Though teachers may align themselves with one or more music education approaches, they must, in the end, define their music education practices

individually. “The Gordon Approach”, therefore, is unique to Gordon himself. Teachers who use Gordon’s Music Learning Theory must examine and develop their music education practices and lead

their students to independent musicianship through audiation. As they do so they refine their music teaching and learning methods while using developmentally appropriate techniques.

Summary

Each human has the potential to learn music through audiation. Ideally, informal music guidance and audiation development begin as early in life as possible. Teachers who practice Music Learning

Theory must be aware that students, regardless of age, need guidance through the types and stages of preparatory audiation before they are ready for formal music instruction based on skill

learning sequence, tonal learning sequence, rhythm learning sequence, and pattern learning sequences. As children exit the types and stages of preparatory audiation and begin to function in

tonalities and meters, school music instruction may be approached as a period of developing music listening, performing, and audiation/improvisation vocabularies through movement, rhythm, speech,

singing, and percussion instrument activities as children progress that lead to meaningful music reading and writing.

When using Music Learning Theory, teachers assist children in becoming independent musicians through audiation. Audiation is music thinking. When children audiate, they do more than remember

pitches, intervals, durations, or rhythms. They think tonal patterns and rhythm patterns in the contexts of tonalities and meters, respectively. Through a whole-part-whole learning process,

children develop movement, rhythm, and tonal vocabularies as they are guided through sequential audiation processes of music imitation, generalization, creativity, improvisation, reading,

writing, and composition through learning sequence activities and classroom activities (Gordon, 2007b, 2007d). Throughout music skill development based on the tenets of Music Learning Theory, the

focus is music learning processes, rather than music products.

Background

After playing tuba and string bass in the Army, playing string bass with the Gene Krupa Band, earning a bachelor’s and master’s degrees in string bass performance from the Eastman School of

Music, and earning a second master’s degree in from the Ohio University College of Education, Edwin E. Gordon accepted a fellowship at the University of Iowa. When first arriving in Iowa, Gordon

taught music, early childhood through grade 12, in The University Laboratory Schools while completing graduate studies and teaching undergraduate music methods courses at the University of Iowa

during the 1950s. While doing so he became extremely interested in how humans learn when they learn music. For 16 years at Iowa, first as a doctoral student, and then as a professor, Gordon

investigated music learning processes and developed the Musical Aptitude Profile (Gordon, 1965/1995), the Iowa Tests of Music Literacy (1971/1991), and The Psychology of Music Teaching (1971),

where he first introduced Music Learning Theory (Gordon, 2006, 2007b, 2007c, 2007d).

From 1972-79 Gordon (2007b) taught and conducted research at the State University of New York in Buffalo. During that time he continued his investigations of music learning processes and

developed Learning Sequence and Patterns in Music (1976), the Primary Measures of Music Audiation (1979) and the Intermediate Measures of Music Aptitude (1982).

After leaving SUNY-Buffalo, Gordon (2006b) became director of the doctoral program at Temple Unviersity in Philadelphia, PA where he held the Carl E. Seashore Chair for Research in Music

Education from 1979-1997. While in that position Gordon continued his objective study of music aptitude, publishing the Advanced Measures of Music Audiation (1989), and Designing Objective

Research in Music Education (1986). He also extended his interests in early childhood music development, publishing A Music Learning Theory for Newborn and Young Children (1990/2003) and Audie

(1989).

Gordon currently collaborates with several authors who develop the practical application of Music Learning Theory for a variety of music education settings from early childhood, Jump right in:

The early childhood music curriculum: Music play (Valerio, et al., 1998), through elementary classroom, Jump Right In, The Music Curriculum (Bolton, et al. 2000, 2001; Taggart et al, 2000, 2006)

and instrumental, Jump Right In, The Instrumental Curriculum, Band, Strings, and Recorder (Grunow, Gordon, Azzara, Martin, 1999-2002). Though retired, Gordon maintains a rigorous international

lecture schedule and continues to publish, most recently releasing, Discovering Music from the Inside Out: An Autobiography (2006), Awakening Newborns, Children, and Adults to the World of

Audiation (2007a) and Learning Sequences in Music: A Contemporary Music Learning Theory (2007b, 2007d).

For Further Information

Persons who are interested in more information about Music Learning Theory may visit http://www.GIML.org, a website maintained by the Gordon Institute of Music Learning (GIML), a professional

organization that

is dedicated to advancing the research in music education pioneered by Edwin E. Gordon. The purpose of the Gordon Institute for Music Learning is to advance music understanding through audiation. We believe in the music potential of each individual, and we support an interactive learning community with opportunities for musical and professional development. (http://www.giml.org/aboutgiml.php).

The website contains information about Gordon’s lecture schedule, workshops, conferences, resources, publications, and GIML certification. GIML certification is available for early childhood

(levels 1 and 2), elementary general (levels 1 and 2), and instrumental.

The Edwin E. Gordon Archive is located in the Special Collections of the Music Library at the University of South Carolina at the following website:

(http://www.sc.edu/library/music/gordon.html/). The collection maintains copies of most of Gordon’s publications, dissertations he advised, and recordings of his lectures and seminars.

References

Azzara, C. D. & Grunow, R. F. (2006). Developing musicianship through audiation. Chicago: GIA.

Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2000). Jump right in: The music curriculum, book 1 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2001). Jump right in: The music curriculum, book 2 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Bruner, J. (1983). A child’s talk: Learning to use language. New York: Horton.

Gordon, E. E. (1965/1995). Musical aptitude profile. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (1970). Iowa tests of music literacy. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2001). Jump right in: The music curriculum, reference handbook for using learning sequence activities. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (1976). Learning sequence and patterns in music. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (1979). Primary measures of music audiation. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (1982). Intermediate measures of music audiation. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (1986). Designing objective research in music education. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (1989a). Advanced measures of music audiation. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (1989b). Audie. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2003). A music learning theory for newborn and young children. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2006). Buffalo: Music learning theory/resolutions and beyond. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2006). Discovering music from the inside out: An autobiography. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2007a). Awakening newborns, children, and adults to the world of audiation: A sequential guide. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2007b). Learning sequences in music: A contemporary music learning theory. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2007c). Learning sequences in music: A contemporary music learning theory: Study guide. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon, E. E. (2007d). Lecture cds for learning sequences in music: A contemporary music learning theory. Chicago: GIA.

Gordon Institute for Music Learning. (2007). About GIML. Retrieved from: http://www.giml.org/aboutgiml.php

Grunow, R. F., Gordon, E. E., Azzara, C. D., & Martin, M. E. (1999-2002). Jump right in: The instrumental series, for band, strings, and recorder. Chicago: GIA.

Reynolds, A. M., Long, S., Valerio, W. H. (in press) Language acquisition and music acquisition: possible parallels. In E. Smithrim & R. Upitis (Eds.), Research to Practice: A Biennial

Series. Volume 3. Canadian Music Educators Association.

Reynolds, A. M. (2005). Guiding early childhood music development: A moving experience. In M. Runfola & C. Taggart (Eds.), The development and practical applications of Music Learning

Theory (pp. 87-100). Chicago: GIA.

Taggart, C. C., Bolton, B. M., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2004). Jump right in: The music curriculum book 3 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Taggart, C. C., Bolton, B. M., Reynolds, A. M., Valerio, W. H., & Gordon, E. E. (2006). Jump right in: The music curriculum book 4 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: GIA.

Valerio, W. H., Reynolds, A. M., Bolton, B. M., Taggart, C. C., & Gordon, E. E. (1998). Jump right in: The early childhood music curriculum: Music play. Chicago: GIA.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Wendy Valerio is Associate Professor of Music and Director of the Children's Music Development Center at the University of South Carolina School of Music. She holds M.M. and Ph.D. degrees from Temple University where she worked with Dr. Edwin Gordon in the Temple University Children’s Music Development Center. Dr. Valerio is a member of the Gordon Institute for Music Learning Mastership Certification Faculty